(A makeover: the before version. Here’s the after.)

In my collection of job aids, there’s a special place for a particular set of assembly instructions. I’ve created a fictional version so as not to embarrass whoever created the original, and to show ways that even extremely inferior job aids can be improved.

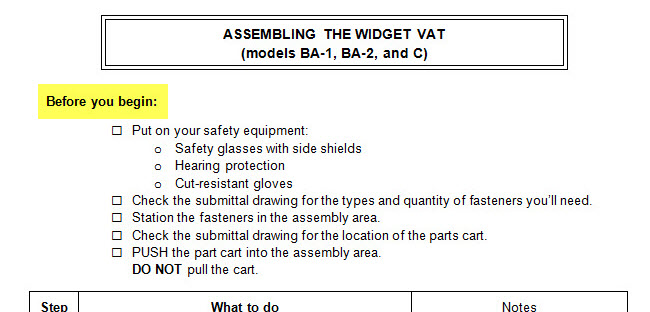

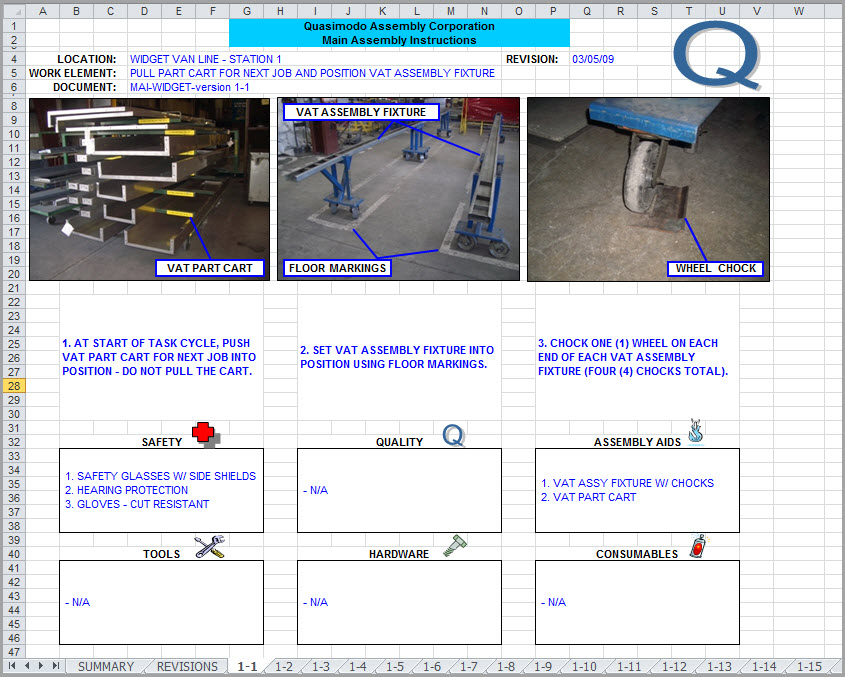

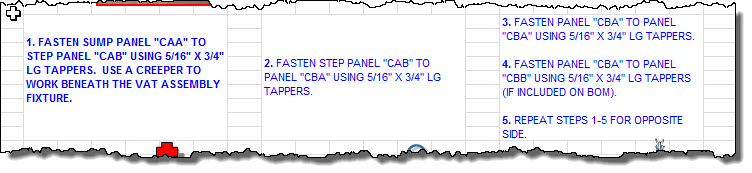

That original was a set of instructions for assembling a piece of industrial equipment that I call the widget vat. Here’s a sample page (which you can click to enlarge):

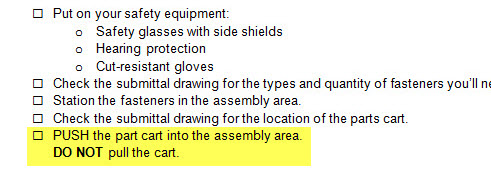

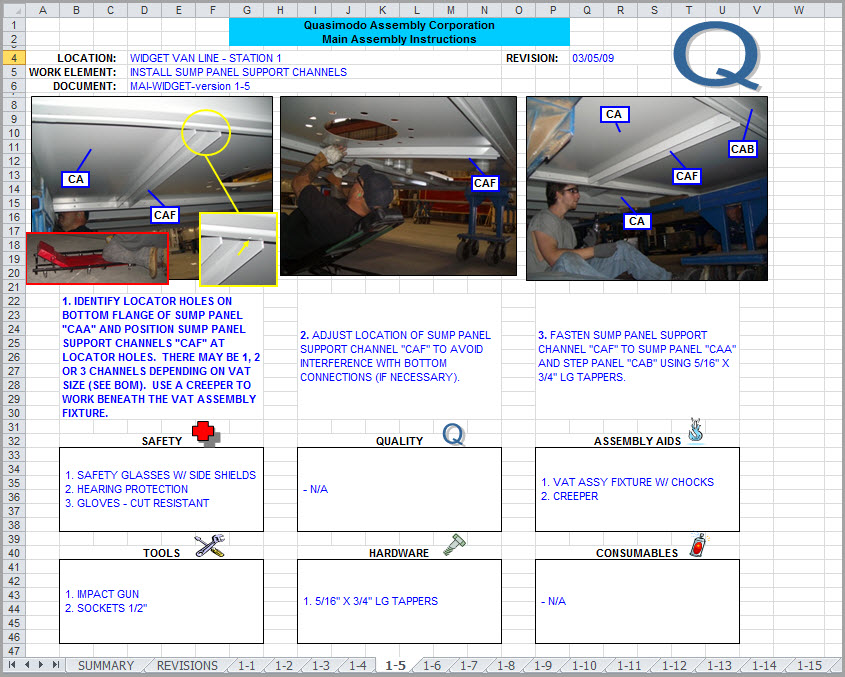

I’ve fictionalized this, as I said. There is no Quasimodo Assembly Corporation, so far as I know, and I’ve altered other identifying bits of information. Otherwise, the layout is identical to the original. That’s page one above; here’s page five:

This job aid has a carload of problems. One of them–and by no means the most important–is that it was created in Excel. Let’s look at some of the others.

Background on the assembly guide

Suitability: what’s this job aid for? What’s its purpose?

You can ask that question from a performance-support point of view: what’s Quasimodo Assembly trying to do, and how could this job aid get it done?

The granular version is: they want to guide workers who are assembling widget vats. True so far as it goes, but I think a sharper focus comes from the desired results. I never spoke with anyone at Quasimodo, but I feel safe in expressing their goal this way:

Produce assembled widget vats that pass inspection and meet cost guidelines.

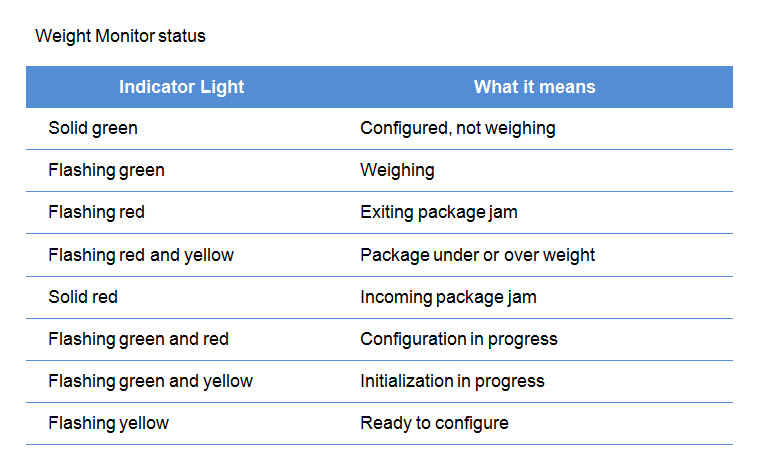

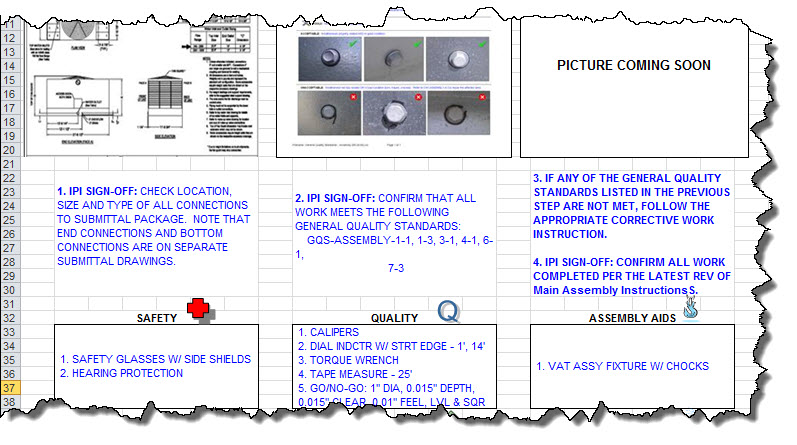

In fact, the original includes (on page 16 of 17) that kind of information:

I haven’t posted all seventeen pages, but it’s clear that this document was meant to guide two or three people, working in a factory, through the process of assembling a piece of equipment that would fill a roomy parking space. Those people handle the job from start to finish–this isn’t something that moves down an assembly line. The process involves more than 50 steps, and several of those are variations on “repeat steps 1 to 5 for all four edges.”

Task details

Many of those steps are sequences of actions with few decisions:

- Position center end wall panel CAD on seembly fixture.

- Use two people or a jib crane to life panels.

- Check submittal [an assembly document ] for end wall connection and bottom connection orientation.

- Fasten center end wall panel CAD to floor plane using 5/16 x 3/4 LG tappers.

- Fasten center end wall panel CAD to floor support channel ZCA using 3/8 x 1-1/4 LG screws.

- …and so on, and so forth…

My guess is that the instructions were printed, perhaps with the pages stuffed into sheet protectors and stored in a ring binder at the assembly area. So, like most procedural job aids, they’re like a recipe.

99 problems, and Excel’s just one

Since the assemblers weren’t using Excel when consulting the guide, this deranged choice for creating it doesn’t matter all that much to them. Using Excel for text layout, however, needlessly and foolishly complicates the task of updating, revising, and even searching the source document.

More than that, layout is not even well-done within the parameters of Excel. Here’s a detail from page 5, above. Note that there are two callouts labeled CA. The accompanying text refers to CAA, CAB, and CAF.

If you had the original file, as I do, you could enlarge those callouts–the text just ran outside the space of the callout box. The assemblers could not. Whoever created this was, let’s say, not at high strength for proofreading.

The real reason that Excel is a poor choice here, though? Nothing calls for Excel. There isn’t a single calculation in the entire document. You might just as well have created the guide with photos of alphabet-letter magnets arranged on your fridge.

Other drawbacks (and they are many)

From a graphics standpoint, the widget vat guide stolidly assigns equal weight to task photos and procedural steps. They get the same amount of space, whether they need it or not.

Similarly, half of each page is take up by six equal-sized boxes, one of which (“quality”) reads “n/a” on every page but one.

So most of the time, a third of the page is doingnothing–other than confining the actual instructions to an all-capital prison.

Other barriers to effective performance:

- “Before you begin” information (like equipment you need and parts you should have) comes after the steps of the procedure.

- Visuals are marooned in a reserved parking space instead of positioned near the step they illustrate.

- Actual steps (the heart of a procedure) are distributed across a trio of all-caps, non-indented, top-to-bottom centered boxes:

Did you notice in the detail that step 5 says “repeat steps 1 – 5?” No doubt the assemblers figured out that they didn’t need to repeat that forever, but no thanks to the designer of the guide.

* * *

In summary, the widget vat assembly guide is hard to read, hard to follow, and hard to update. It’s not going to improve the process of assembling vats, at least not till the workers have done enough of them that they don’t need the guide any more.

In the next post, we’ll move on to what we’d change and why we’d change it. Spoiler alert: we won’t be using Excel.