About the QRH for Engine Dual Failure

On January 15, 2009, US Airways flight 1549, an Airbus 320, lost thrust shortly after takeoff and ditched in the Hudson River. The following year, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) issued its report on the incident (summary, full report).

Thirteen seconds after the plane struck birds, captain Chesley Sullenberger told first officer Jeff Skiles, “Get the QRH [Quick Reference Handbook] loss of thrust on both engines.” (Skiles had recently been to recurrent training, and so Sullenberger believed the first officer could find the QRH more quickly.)

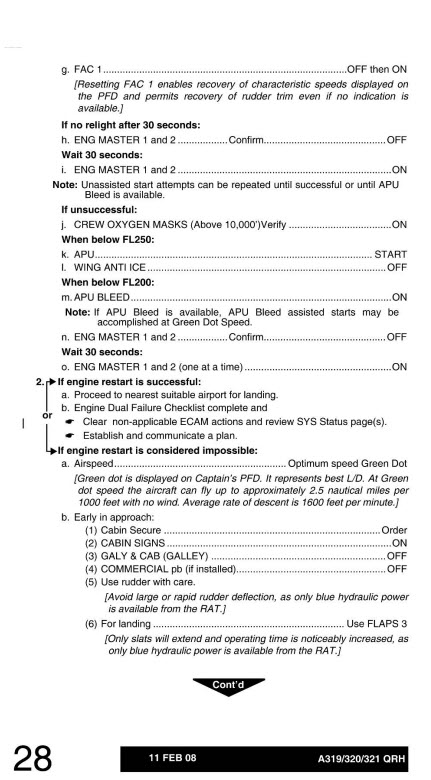

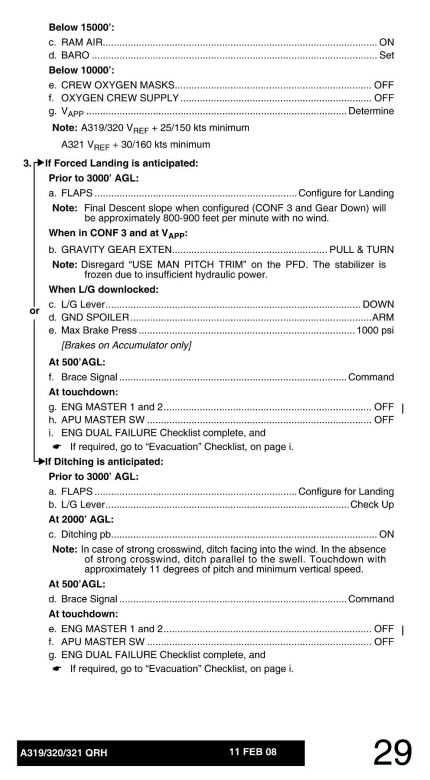

In everyday speech and in news reports, such tools are often called checklists, but because the Engine Dual Failure quick reference involves a sequence of actions, as a job aid I consider it a procedure. It’s a guide through a number of steps to follow when both engines of an Airbus fail.

Accomplishment

At one level, the accomplishment here is to safely land the aircraft following the failure of both engines. Looking deeper, you can see that there are decision paths build into the quick reference.

Step 1 has to do with fuel.

- “If no fuel remaining…” has eight substeps to complete before going on to Step 2.

- “If fuel remaining…” is even more complicated, with internal decisions based on type of aircraft, ability to reach Air Traffic Control, result of trying to relight (restart) the engines; the longest path has fifteen substeps.

Step 2 (on the second of the three pages) hinges on whether the attempt to restart the engines was successful.

Step 3 deals with whether the aircraft will have a forced landing (that is, on the ground) or a ditching (an emergency landing in water).

Performer

This is a highly specialized job aid, intended for use by the flight crew of particular Airbus aircraft. It’s full of technical shorthand (FAC 1, OFF then ON; ENG MODE Selector, IGN) and directions aimed at skilled people (“Add 1° of nose up for each 22,000 lbs above 111,000 lbs…”).

Coping with emergencies: a performance dilemma

In an emergency, one risk is tunnel vision: becoming so engrossed with certain aspects of the situation that routine ones get overlooked. Job aids are one way to address this–if the performers are trained to rely on the job and, and the work culture emphatically supports their use, then it makes sense to store information and guidance in the job aid.

Skills that are time-critical, like the actual flight maneuvers, are the ones that you spend time learning (storing in memory).

The NTSB report acknowledges this, and notes a performance dilemma:

Accidents and incidents have shown that pilots can become so fixated on an emergency or abnormal situation that routine items (for example, configuring for landing) are overlooked. For this reason, emergency and abnormal checklists often include reminders to pilots of items that may be forgotten. Additionally, pilots can lose their place in a checklist if they are required to alternate between various checklists or are distracted by other cockpit duties; however, as shown with the Engine Dual Failure checklist, combining checklists can result in lengthy procedures. [NTSB report, p. 92]

Comments

I’ve written about Flight 1549 on my other blog. Some aspects are relevant to the example of this quick reference. For example, the reference assumed a higher air speed and a higher altitude than Flight 1549 had.

Sullenberger said later that although there was an additional reference for ditching the aircraft, the crew never got to use it. “The higher priority procedure to follow was for the loss of both engines,” he said in an interview. In other words, in their professional judgment, it was much more important to try and restart the engines.

So: on the one hand, you can’t infallibly job-aid your way through every possible situation. But neither can you infallibly train (work at storing in memory) through them all, either.

Side note: passengers and safety

Talking isn’t training, and listening isn’t learning. Despite the inescapable safety briefing on every U.S. commercial flight, only half the passengers evacuated with their “can be used as a flotation device” seat cushions. 19 passengers also tried to retrieve life vests from under their seats; only 3 succeeded.

And of the 30 who tried to put on a vest once outside the plan, only 4 said they could do so properly.

Nevertheless, without taking anything away from the safe ditching of the aircraft, the evacuation training that the cabin crew regularly underwent (so as to be able to perform from memory) had a great impact, though one much less widely acknowledged, on the survival of every passenger from Flight 1549.